Interview: Jennifer Sherman Talks Localization and Editing

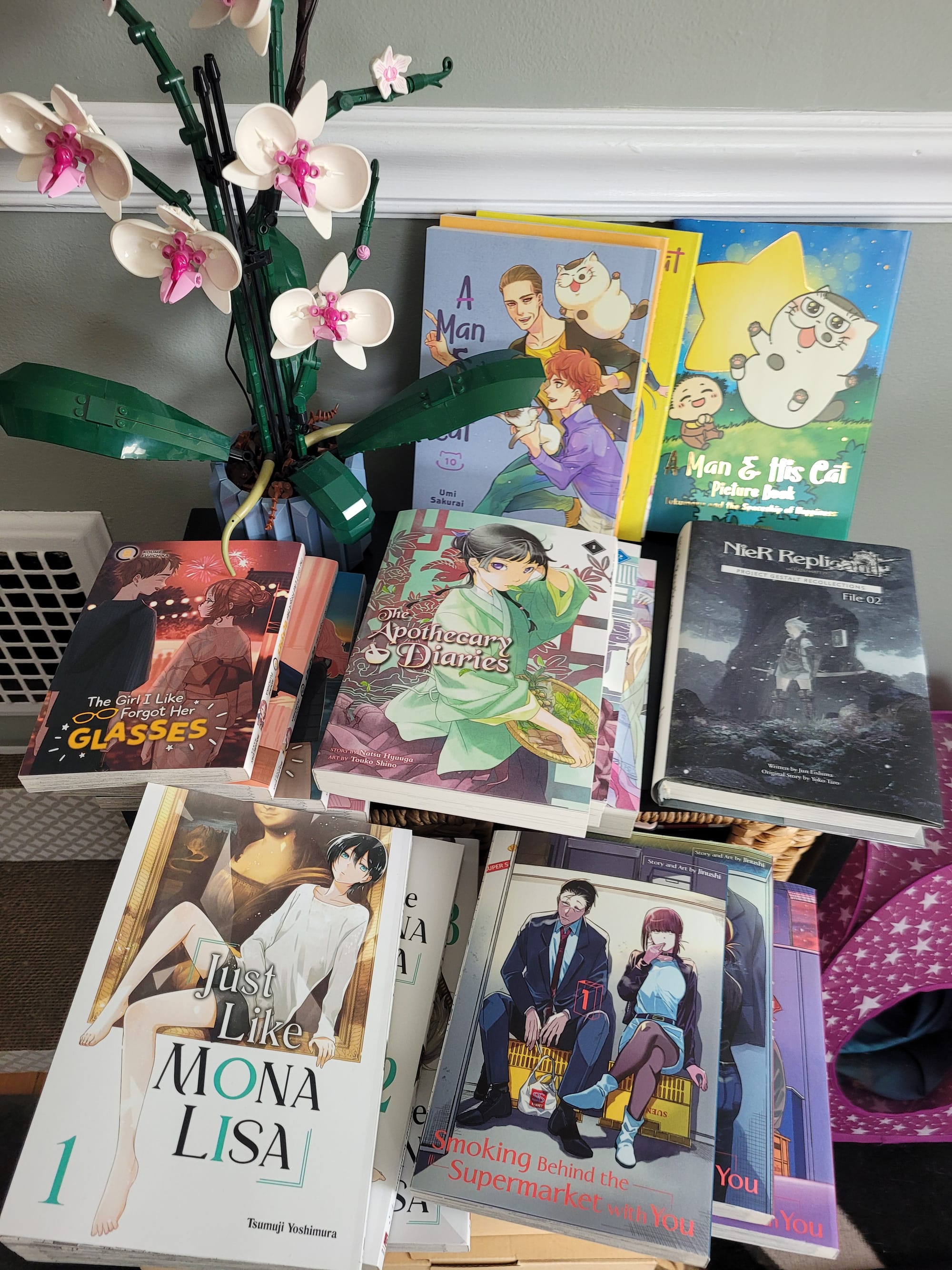

For Anime Atelier's first-ever interview, we had the honor of chatting with editor and localizer Jennifer Sherman. Although known for her editing work on Square Enix titles such as Smoking Behind the Supermarket With You, Just Like Mona Lisa, and Victoria’s Electric Coffin, Sherman actually spent a decent chunk of her career at Anime News Network, making her a familiar face in both the industry and fandom.

We got to discuss not only her work and the effect AI-translating will have on the industry, but also learn more about the technical details of manga publishing and some other fun tidbits.

Q: You went from anime fandom to the news scene to the publishing industry. Would you say that this was a natural progression? What helped you acquire the skills to get you to where you are today?

For me, it was a natural progression, but it might not be for everyone. There are a surprising number of ways people in the manga and light novel publishing industry find their way in. I became an intern at Anime News Network and immediately started honing my translation, writing, and editing skills. I studied style guides as they related to my work.

When I began my almost ten years at ANN, I didn’t really plan to be an editor in the long-term. When I was in college, I think I imagined myself becoming something like an anime translator. Although my focus is now mostly manga and light novels instead of anime, I still use my Japanese language skills every day on the job—just not with the job title I would have guessed.

Living in Japan on the JET Program also helped solidify my language skills and cultural awareness. After I came back to the U.S., I knew I still wanted to be involved in localization, but I didn’t feel ready. Eventually I got brave enough to apply for freelance editing positions after continuing to improve my skills on the job and through certificate programs. In hindsight, I could have progressed in this direction much more quickly if I’d been brave enough to apply earlier.

Q: Complaints about translations and localizations seem to be rampant in the community today. What do you think creates this discontent and disjointment between the audience and those tasked to bring it to them, the translators and localizers?

It’s a complicated issue that seems to become more fraught all the time. Part of it is that some consumers are relatively savvy and know some Japanese. As an example, you don’t tend to see waves of negativity surrounding the wide variety of translated literary fiction available in English. Part of that might be because readers of those books aren’t necessarily studying the original languages they were written in. When it comes to things like anime and manga, though, the fans are often studying Japanese. The fans tend to think of themselves as insiders in a certain respect, and for some, that can make them hypercritical of translation choices. Japanese is one of the most commonly studied languages in the U.S. I wish everyone was interested in language learning, but it’s also important to note that having knowledge of a language and practicing the art of translation are two distinct skills. Analysis is good, but localization is not as straightforward of a process as some people think. We usually can’t share all the details, but there are often factors involved in translation choices fans might not realize. For one thing, it’s common for licensors to set how terms are translated on certain projects, and those terms cannot be changed.

The culture around fan translations can also contribute to discontent among fans in the end. If a work has a fan base for many years before it’s available legally in someone’s native language, they start to build up expectations about what a release of that work will be like when it does get an official release. There may be many reasons why a licensed, official release differs a lot from fan translations, but publishers usually can’t publicly talk about them.

Q: Do you feel changes have been made in the industry practices to try and address these issues?

I think some changes have been made in the sense that publishers are trying to reach out and connect more with fans in new ways. You see that mostly on the social media and marketing side, though. There’s only so much publishers can do when there are other factors in play, and ultimately they have to answer to licensors.

Q: AI and MTL have been heavily advertised as a quick and cheap solution for translation and many publishers seem to have embraced these technologies as a cost-cutting solution. What kind of role do you think these will play in the future? Do you expect them to become a useful tool or will we keep progressing towards fully AI-translated content with “human” editing?

Well, I hope the role these sloppy AI and MTL cost-cutting ventures have in localization in the future is none—at least not in any kind of iteration that they’re working with now. Many of us in this industry hope this is a passing fad that goes the way of NFTs and crypto once the tech bros realize it’s not really going to catch on.

Generative AI in its current usage has created a modern crisis in the arts. It steals content from human creators and destroys the environment in the process of regurgitating content that passes as a meaningful creation or plausible solution to a prompt it’s given. Also, many people are also unable to detect the great lie in genAI content, and it masquerades as the product of actual minds. And one might think machine translation post-editing (MTPE) could be a useful middle ground, but the reality is often different. It takes humans more time and effort to fix machine-translated content than it would for them to have done it from the start much of the time. Because of that, it ends up costing companies more money in the long run than if they’d just relied on human beings from the get-go.

The words of another Jenn in localization from a recent LinkedIn post sum it up succinctly:

Q: What do you pay attention to the most when you face a tricky translation, for example, a colloquialism that makes sense in Japanese but not English? Do you have a favorite example of such a situation?

Colloquialisms, idioms, and humor are when translators get to show off that they’re skilled writers first and foremost. I wish I’d kept a list of really clever translations of colloquialisms, but, alas, I haven’t so far. For people who are interested in this sort of thing, I recommend following the social-media pages of translators. For example, you could look at who’s credited on the copyright pages of your favorite manga series. Some translators share their process, and you get to see behind the curtain of really brilliant translations!

On a slightly different note, one amazing linguistic marvel made the rounds among my fellow editors recently. It’s a Japanese-English portmanteau that astonishingly appeared in the original Japanese. “Gomenna-sorry.” It’s a very rare occasion when we can keep the original Japanese phrasing and have it also be a perfect English translation.

Q: What would you say are the main differences between editing a digital release and a release for print?

If you mean the difference between a printed book and its digital version in the traditional process, normally there’s no difference. We take it through the editing process once, and the print version becomes digital. There are many unique projects, but that’s generally how the process works.

Content made for dedicated digital formats, though, can have different restrictions than print. Plenty of modern manga releases get digital simul releases. Editing under those limitations can be a big challenge because you might only have a week from getting the files until they need to be published. With manga, that means you have to compress the process of translation, lettering, editing, and formatting the files into a very limited time period. If that series gets a print release later, you can go back and edit again, change the lettering, and potentially improve the product for print. Not all digital-only releases operate on such tight schedules, but budget or other factors could also influence the approach, which might be different if it was destined for print. One good thing about digital releases is that if a mistake does go public, you can edit it on the back end, and it’ll automatically be updated for users. If there’s a mistake in print, you’re out of luck for the most part and have to hope that the book gets a reprint that would allow you to fix the issue.Q: What is it like working on The Apothecary Diaries, which has already been translated and edited once by J-Novel Club by their team, compared to a project where you’re bringing it into English for the first time with your team?

Working on the print version of The Apothecary Diaries light novels is a treat for me. I love the story and especially Maomao, and I particularly like working on light novels in general. This is a unique project, though, since the digital and print versions have different publishers. It’s no secret since you can read the credits on the copyright pages, but we use J-Novel Club’s translation as the basis for our print release at Square Enix Manga & Books. We still have to do the standard editing processes to do our due diligence on a project like this that’s already been published. Even though it’s already been published, the time frame for producing such a project can end up about the same as if we were doing it from scratch because of all the editorial and production processes involved. When you create a translation from the beginning, there are more firsthand developmental discussions that affect the foundation of the translation. Issues, challenges, and questions still come up with a secondhand project like this, but the focus is more on the polish and making any adjustments for the work’s new format.

Q: What has been your most challenging project to work on?

As editors, all of our projects become our babies, but some are closer to “problem children” than others. One of the biggest recurring variables that makes projects challenging is time. For mainstream publishing, an editor could work with an author on a single book for years. We don’t have that kind of time in the world of manga. As a personal example, Dragon Quest: The Adventure of Dai was particularly challenging because it was on a bimonthly schedule in addition to having long volumes and fairly complex art. Working on simulpubs can also be stressful because of time. On the other hand, the difficult projects can be the most satisfying and rewarding when they’re complete.

Q: Which of your projects have you enjoyed the most?

You would ask me my favorite child, wouldn’t you? I’ll just say that some of the projects that bring me the most joy right now are the ones that feature cats in various forms.

Q: Do you have any tips for people looking to start out in the manga/light novel publishing industry?

For those interested in translation, take some of your favorite works and translate them on your own, then analyze your choices alongside the official translation, if possible. Letterers can use the same method with their craft. When you’re more confident, you can hold on to some of your favorite samples (without posting them online!), and privately use them as a portfolio with applications. To clarify, practicing translation skills can be as important for editors in localization as it is for the translators. Various members of the localization industry, including the aforementioned Jennifer O’Donnell, also have great websites full of advice and tips.

For manga and light novels, the foundation you need is the same as any arena of book publishing. Editors can study style guides like The Chicago Manual of Style, and writing and reading as much as possible is always sound advice. Don’t be afraid (like I was initially) to start applying for positions! I also regret to say that networking is important. Knowing someone, even loosely, at a company can make all the difference in the world when you apply because you’ll be much more likely to get human eyes on your application. Reach out and chat with people! Just don’t make it overly one-sided or seem like you’re only milking the person for a job. That said, you might be surprised at how many people, like me, are happy to talk about our industry.

We'd like to thank Jennifer for taking the time to answer our questions in such detail. People who are passionate about manga and light novels and who actually work in the publishing industry are a rather valuable addition to the fandom and should be more appreciated. We look forward to seeing what other titles Jennifer has a hand in bringing to us in the future!

In the meantime, you can find Jennifer on Twitter/X and Bluesky.

Images courtesy of Jennifer Sherman.